Stone Pillars at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History

- oliviaallendxb

- Jun 15, 2023

- 6 min read

The Oxford University Museum of Natural History (OUMNH) is a really rather wonderful place. Situated on Parks road about a 3 minute walk from the Earth Science department it is very handy for us to just pop in. The museum has a brilliant collection of geological specimens and its been so cool to see how I've gone from not really knowing what anything is to being able to bore various family members with random facts about the rocks and fossils when I drag them round it with me. Definitely nice to see that I am actually learning something from my degree!

Pillars at the top floor of OUMNH looking down over the main atrium

Over the course of the last two years I have had a number of tutorials, lectures and practical classes in the museum. A particularly cool practical session this year involved us going 'behind the scenes' and looking at a bunch of trace fossils from the museum's collection (trace fossils are basically fossil evidence of organism behaviour so footprints or burrows etc). The museum has a really cool collection and it was great to get to look in depth at some of the specimens. In my first year we also got to go to the museum to look at some of the meteorite samples they have which needless to say was very very cool.

Another photo of the museum showing some of the specimens on display

Our first ever tutorial in the museum was in maybe the second week of our degree and didn't involve looking at any of the museum specimens. Instead we spent an hour looking at the pillars.

Each pillar inside the museum is made of a different type of stone. In this tute we had to sketch the pillars and discuss with our tutor different observations we made to try and figure out the type of rock. As we were silly little freshers we still didn't know much about rocks at all or how to identify them but it was a fun introduction to making observations of actual specimens which we would then go on to put into (maybe too much) practice in the field.

Now, whenever I take someone new to the museum (my boyfriend getting the joys of that this past week) I like to point out the different pillars and how they are all different types of rock. Below are a selection of the highlights of these pillars for you to see for yourself.

PS. Excuse the awful lighting in some of the photos, I do not claim to be a good camera woman in the slighest.

1: A Granite pillar from The Ross of Mull, Scotland

As you can see above, each pillar has its rock type/name and where it is from engraved into the stone at the bottom. This would have been incredibly useful to our rock identification tute however this is only written on the outside of the pillar and we went round the inside so there was unfortunately no assistance to us there.

Granite is an intrusive (formed by cooling slowly underground rather than quickly at the surface) igneous rock. See my article on rock types if you wanna know more about what that means. Granite is one of my favourites because the potassium feldspar makes it look quite pink so is quite easy to recognise. This particular pillar was the first one we had to sketch in the tutorial and I at the time did not have a clue what I was looking at. I remember being rather confused about where to even start with my sketch but I am happy to say I have somewhat refined my skills since then and now I reckon I could give it a much better go.

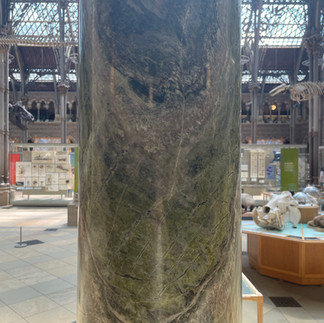

2: Ophicalcite from Connemara, Ireland

This pretty green coloured rock is an ophicalcite which essentially means that it is a metamorphosed rock comntaining serpentine and carbonate (calcite) minerals. Serpentine often forms when olivine ( a common mineral in ocean crust) is exposed to water. It is the serpentine that makes the rock green.

I was particularly excited by this pillar because it comes from Connemara in Ireland. In less than 2 weeks time I am heading off to the west coast of Ireland, near Connemara to complete my 6 week mapping project which we have to do as part of our undergraduate degree. Subsequently, I have been doing a lot of reading up on the rocks of western Ireland in order to have a vague clue of what I'm looking at when it comes to the mapping. I have a hunch that some ophiolites/ophicalcites such as the one above may outcrop in the area I am working in.

Here's another Ophicalcite from County Galway (actually even closer to my mapping area):

3: Carboniferous Limestone from Garsdale, Yorkshire

There is a whole bunch of Carboniferous limestone pillars in the museum from various places in the UK. A couple others are pictured below.

Carboniferous limestones just mean they are limestones that were deposited (laid down and became a rock) in the Carboniferous period of Earth history about 300-350 million years ago. Limestones like this are typically deposited on the seafloor. The one above contains lots of fossils (which you can maybe just about make out). Particularly notable fossils are crinoid ossicles (parts of the 'stem' of a crinoid which was an animal that lived on the sea floor and is sometimes known as a sea lily because they looks a bit like a flower).

A fun fact about this particular rock is that it is from the same formation that my mum's new kitchen counter tops come from. This means that our kitchen counter tops have loads and loads of fossils in them which is beyond cool in my opinion! Also is great fun to point them out and bore my family with fun fossil facts whenever someone is cooking

Here are some more carboniferous limestone pillars:

As you can see they come in a bunch of different textures and colours. However, they were all deposited during the Carboniferous and are all made of primarily calcite so classify as Carboniferous limestones just with varying degress of metamorphosis, fossil content and accessory minerals (other minerals that are present in smaller amounts).

4: Quartziferous Porphyry from Cornwall

A number of pillars in the museum are made up of rocks described as porphyry or porphyritic. This term refers to the fact that they contained coarse grained crystals amongst a 'groundmass' of finer grained crystals. In igneous rocks these coarser crystals are known as phenocrysts but in metamorphic rocks they are known as porphyroblasts which is what I use to remember what a porphyry is (the words sound way more simillar).

This Cornish porphyry is quartziferous which simply means it contains the mineral quartz.

Here is another example of a porphyry pillar, this time a hornblende porphyry from Inveraray in Scotland. As suggested by the named, it contains the mineral hornblende which is a type of amphibole.

The final example is a porphyritic granite, so a granite that has some more coarse grained crystals. The porphyry would have formed via different crystals cooling at different stages. If a crystal cools more slowly it will be bigger as it has more time to grow, finer grained crystals will have cooled much quicker.

This particular pillar was on the edge of the museum gift shop, hence the cuddly dinosaurs :)

5: Gabbro from Aberdeenshire in Scotland

Gabbro is what makes up most of oceanic crust. Its a mafic (containing magnesium and iron) rock . Gabbro is the intrusive (cools underground) version of basalt (which cools extrusively at the surface). Gabbro is one of my favourite rocks, even to the point that I named my car (yes yes, I named my car don't come at me) Gabby because she is somewhat the colour of gabbro.

6: Triassic Breccia from Somerset

The final pillar I have to show you is this Triassic Breccia from the Mendip Hills. As before with the Carboniferous limestone, the Triassic part of the name just means it formed during the Triassic period about 200-250 million years ago. The breccia part of the name is talking about the type of rock. Breccias are rocks made up of angular clasts (bits of rock) cemented together by a fine grained matrix. These are often formed after a rock is weathered but he smaller bits of rock formed (that will then become the clasts of the breccia) are not transported very far. Transporting the clasts further tends to round them off the same as if you were rubbing them against sandpaper.

Breccia can also form in geological faults (known as fault breccia). Seeing these is the field is very diagnostic of a fault and great content for your field notebook. Grinding of each side of the fault against each other causes them to break up and form the clasts that then form the breccia.

So thats it for my little display of pillars at the museum. If you're in Oxford I would definitely recommend giving OUMNH a visit! Its very interactive and has loads of cool specimens from dinosaur fossils to meteorites and way more. Heres a link to the website if you want to find out more: https://www.oumnh.ox.ac.uk/

All photos were taken by me during my latest visit to the museum.

Comentários